- Home

- Byrd, Sandra

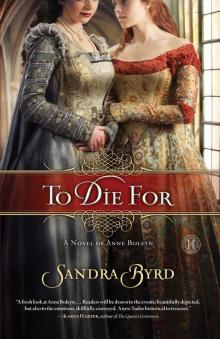

To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn Page 3

To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn Read online

Page 3

I hugged her quickly and pulled away. “I’m eager to hear all of your news.”

“And there is news…,” she added tantalizingly.

“There’s always news with you,” I said, grinning. “Oh—I almost forgot. From Thomas.” I pulled the scroll out of the sleeve I’d used to smuggle it in.

“Oh, Meg, he’s still sending poems.”

“Yes, I know. I’ve told him he must let you go.”

“And so he must. He’s a dear friend to me…. but naught else.”

“I know,” I said. “Dance with him once at Mary’s wedding feast and then tell him he must move on.”

I took my leave and rode back home quickly with my manservant to beat the darkness. Once home I handed my wraps to my maid, Edithe, and then went upstairs to check on my mother.

Her chamber was darkened, as it almost always was these days. I’d spent a good amount of time with my sister, Alice, in the past year or two, staying at her household for months at a time and then returning to Allington to help my mother manage the household and her affairs, which I didn’t mind at all, for her sake. But she’d purposefully placed more and more of the daily concerns into the hands of her trusted lady servant, who had been with my mother since she was a child.

I didn’t know if it was her pain or her mood that made her desire the darkness. “Shall I open your tapestries a bit to let in the last light of the day, my lady?” I asked softly as I came into the room. She nodded weakly and I pulled them back. The effort released dust, and the motes floated to the ground in a gentle downward drift, symbolic of my mother’s state of being. It was clear she was not going to make it to dine this evening.

“Tomorrow is Mary Boleyn’s wedding celebration.” The ceremony itself had been some months past but Sir Thomas wanted to show off his fine gardens while they were in bloom. I sat on the edge of her bed and stroked the hair by her temple. I waved to her lady servant, dismissing her to rest for a time. “And the king is coming!”

“I fear I shall not be able to attend,” my mother answered. “This day I am too weak to sit aright in bed, much less dress to be seen.”

I tried not to show my alarm. My sister was in London, her ninth baby due to arrive any day. Thomas would escort his intended, and if my mother didn’t go, my father wouldn’t, either.

Which would leave me at home with the loathsome Edmund, who would amuse himself, I was sure, by lowering his boot on live insects to hear them crunch and then see them squirm and die.

“Are you certain?” I looked into her face, which, over the past months, had gone from mothlike white to a slowly hardening mask of wax gray.

“I am certain,” she said. “But I will ask your father if he will allow Thomas and his wife to escort you to the wedding. I know you want to see your friends.” She reached out and took my hand in hers; it was papery and dry, the skin pulling into folds that did not recover to smoothness. “I have a gift for you, Meg. Call Flora.”

I kissed her hand before letting go of it and then rang the bell to indicate that we required a servant. When her servant came my mother sent her for the seamstress, who soon returned with a large dress box.

“Bring it here,” my mother whispered, and then indicated for me to lift the lid. I did, and pulled out the most amazing gown of russet silk, the perfect color to set off my hair and eyes. It was trimmed in cord that I knew to be copper but glinted dangerously close to the gold only allowed to royalty. The kirtle underneath was ivory, as were the ruffs. It was cut in a French style but not a copy of one of Anne’s.

“Oh, Madam!” I said. “This is too beautiful for me, for a simple country celebration. Thank you, thank you.” I reached forward and hugged her, her skeletal frame somewhat cushioned by the layers of bedclothes.

“’Tis no simple country affair when the king will attend,” my mother replied, smiling. The first real joy I’d seen in her eyes for quite some time then dimmed. “I fear I shall not be here to see you wed and have that dress made.” She coughed and I saw the brown phlegm though she tried to quickly fold the kerchief in half to hide it.

“Father wants me to marry soon.”

“It will take time to arrange, but he will find someone highly placed and who owns vast properties,” my mother said. “And who knows? Your husband may end up being kind.”

“But Father is not!” I said, keeping a care not to let my voice rise too much but not tempering my frustration, either. “He beats me senseless and then, when I’m of some profit use to him, he marries me off to the highest bidder.”

My mother flinched at that most impolite word, “profit.” “Do you know why your father suffers so?”

We never discussed my father—any of us. “I’m unsure.”

“As a young man, your father joined in a revolt against that pretender and murderer King Richard. They captured your father and put him in the Tower and tortured him, night and day, for two years. When Henry Tudor, father of our good king, came to the throne, he released your father and rewarded him with lands and titles for his loyalty. But the demons beat into your father never left.”

I said nothing. I was sorry for his torture but failed to see how that left him free to beat me. If it were me, I’d have shied away from torture for having suffered it. Just then I caught the sound of my brother Edmund idling in the hallway, waiting to wish our rarely awake mother, whom he worshipped, a good eve.

It occurred to me that Edmund, like my father, responded to his torment by tormenting others. Only whereas my father’s fits of anger seemed like an ill-restrained impulse, Edmund’s seemed a well-rehearsed pleasure.

My mother’s feeble grasp on my wrist grew weaker. “Mayhap your father wants to marry you quickly for your own good.”

“Mayhap by marrying I advance the Wyatt name.”

My mother nodded. Pain had not clouded her vision. “It would be best for you to remain often with Alice until the time that you are married.”

In other words, after her death, I should get away from my father. I kissed her cheek and a short time later she fell back into the laudanum of sleep. I left, taking my prized dress box back to my own chamber and thankful not to have met Edmund still skulking in some dark corner.

My servant, Edithe, made a show of smoothing my bed over and over, and just as I was about to remark on her odd behavior I saw the scroll. “Thank you, that will be all,” I said softly, and she grinned at me as she left.

Meg was tenderly etched along the side, above the smooth wax that I knew had been sealed by Will. I slid my finger underneath, relishing the knowledge that his finger had touched this very same paper.

THREE

Year of Our Lord 1520

Hever Castle, Kent, England

My father had purchased a fine new litter, so even if he wasn’t attending Mary’s wedding party we arrived in style. Lord Cobham’s sister—I must learn to speak of her as Elizabeth—sat close to Thomas. He recoiled slightly, as someone does when sitting near a sweating sickness victim, though she was perfectly healthy and hale. I understood. I kept a distance from my brother Edmund, who pressed his leg into mine in a menacing manner, taking two-thirds of the bench to my third. I dug my foot into the floor to brace myself from sliding into him.

We pulled in front of the castle and one of the Boleyns’ men let us out. I held up the hem of my new dress so I wouldn’t soil it in the mud and horse muck, both of which steamed into the cool evening air. We four navigated the crowd, quickly making our way on the cobblestone path. The yard was alight with torches and music escaped from the new upstairs great hall, which was very great indeed. Anne’s father prided himself on his entertainment and it was justified.

The minute we got in the door Edmund headed for the mead as he often, and noticeably, did. I scanned till I found Anne, busy acting the part of co-hostess with her mother. I stood to the side and observed her for a while. Her manners and conversation were now those of a French woman: smooth, subtle, wry, sophisticated. She made her way to me.

“Meg!

I must attend to the guests with my mother, as Mary is the guest of honor and unable to assist.”

“Of course,” I reassured her. “We’ll have the evening to talk after the party; our serving men are instructed to bring us home in the morning. Your father has kindly offered his hospitality.”

“Marvelous!” She squeezed my arm.

“You look beautiful,” I told her, and it was an understatement. She wore her hair long and free, as an unmarried woman is allowed to do, an overflow of black silk with teal string threaded through it to match the teal green of her gown. Her skin shone in the candlelight and when I looked more closely I could see she had powdered herself with something that glimmered.

“You look beautiful,” she said. “I’ve never seen a gown that color before nor a cut quite so enticing and modest at the same time.” She turned her head and I followed her gaze. “Rose Ogilvy has arrived. Why don’t you go and talk with her?”

Then she slipped into the crowd effortlessly, like a swan floating on the Thames, moving yet seeming not to move, her long neck and graceful beauty drawing the eye of both men and women as she walked.

The tables had all been arranged, but of course the food could not be served till the king arrived. I made my way toward Rose and she greeted me warmly. “Good evening,” she said. “My brothers are here, both of them. And my father. And my…. intended.”

“Rose!” I exclaimed. “I didn’t know. Who is the fortunate soul?”

She turned her eyes downward but I saw a pleased smile cross her face afore she took cover in humility. “My Lord Blenheim’s son.”

She was too reserved to say it: the heir of Earl Blenheim, the only son of Earl Blenheim. But this was a coup indeed. Her father had noble aspirations for his family and he’d wasted no time, apparently, in placing Rose well. “Congratulations,” I told her. “I wish you the most happiness.”

She lifted her eyes, suddenly more adult-like now that her marriage was settled, and, if I wasn’t mistaken, a bit more sure of herself. Mayhap a bit too sure of herself. Her nose had an upward tilt that I hadn’t detected in the many years I’d known her, and without a word, she quickly took her leave of me to greet one of Queen Katherine’s ladies-in-waiting. She seemed warmly welcomed.

I took a goblet of watered wine from a liveried servant and spoke with my mother’s cousin. As I did, I caught sight of him as he entered the hall from the terraces outside.

Others may have been waiting all evening for the king to arrive, but I had been waiting for Will.

He stood there, a man now, with his brother, Walter, his father’s heir and pride. I watched with, I’ll admit it, relief as Lord Asquith, his father, forcefully steered Walter toward some of the highborn young ladies in attendance, but not Will. Will looked up, caught my eye, and grinned ere he could stop himself. I lifted my pomander to my nose to hide my smile. Fortunatissima!

“Look, Meg!” My cousin took my elbow and directed my attention to the courtyard. A great stomping of horses could be heard and the musicians stopped their songs. A loud herald of trumpets drowned out the clatter and clank of the carriage wheels.

“The king!” A general murmur went through the crowd. I first thought of my poor mother, who had so longed to see the king again, and then had the puniest of kind thoughts for my father, who had stayed home rather than attend without her. Those thoughts were soon gone, though, as I lifted my eyes and looked for the sovereign himself.

Of course I had been to court a time or two, for jousts and for pageants, but that had mostly been when I was younger. My sister, Alice, had taken me to court with her a few times as well but we’d mostly stayed in the ladies’ quarters.

The king.

He strode in, a great, ruddy bear in wine-colored velvet trimmed in gold cord and slashed in gold silk. Sir Thomas, Anne’s father, followed the king around in the most attentive way. I must say, the king didn’t act as I’d expected he would, dignified and quiet. He threw his arm around Sir Thomas, took a great mug of ale and gulped it, threw his hand toward the musicians, and shouted, “Play on!”

He was the height of handsomeness, he emanated power, he completely dominated the room. One could not imagine him anyone but the king. My knees automatically dipped as he walked. He went to the dais, the table set up for himself and, at his insistence, for the bridal party.

Anne’s father indicated that we should sit and eat, and we went to find our places.

Will came alongside me. “I have been looking forward to dancing with you,” he said, and that sent a shiver of reassurance through me. I’d been worried, because the tone of the note he’d sent me through Thomas had been cooler than the others he’d sent, some of which had fairly singed the paper they’d been written on. In the most courtly, appropriate way, of course.

The servants brought out great platters of swan and eel—the king’s favorite. Whole roasted hares were set on each table, as were minced loin of veal with great platters of fat to spread upon them. Bowls of hard-boiled eggs were passed. Though I loved them, I did not take one, not wanting my breath to smell of egg after the evening’s events, though my brother Thomas took three. I shot him a warning look and he popped one more in his mouth, to the dismay of one of our more proper cousins. I did take some spiced wafers, which I also loved. They’d been cunningly made in white and red, cut in the design of the Tudor rose. I heard the king voice his approval when he saw them.

Then I heard him express his appreciation for the bride in an overly familiar way. Mary and Sir William had been married months before but still the king drew near to Mary, beautiful and golden, as the king was known to prefer his paramours. Mary drew closer toward him too. Her new husband looked on in impotent horror. What could he do? Henry was law.

I heard a quiet comment from someone at the end of my table. “’Twas not enough to shame herself with the French king, now she’s going to shame herself with England’s as well.”

There was a mushrooming of approval from those who heard the comment, though I held my face still. Oh, Mary. Please don’t encourage this.

At meal’s end the king claimed the first dance with the bride, who willingly agreed. Sir William tried to look enthusiastic but his earnest face showed his pain. Sir William, you have a steep and rocky path ahead of you.

The servants removed the tables and the musicians began to play. Everyone partnered off quickly. My brother ignored his wife but she didn’t seem bothered; she’d taken up with another man the moment we’d arrived. I could tell she’d had several goblets of wine—probably unwatered. My brother headed straight for Anne, who met him graciously, though a bit coolly.

She was a childhood flirtation, Thomas. I willed him to understand. But he would not.

A moment later I felt a hand on the small of my back. “Have you a partner yet, Mistress Wyatt?” Will asked.

“Do I now?” I responded a bit coyly, I admit, but then a girl is allowed.

“You do.”

The musicians struck up a pavane, and we lightly touched fingers, as all the couples must. For that reason it was one of the favorite dances for those in love or who wished to be. My gowns swirled along the floor as we danced. Though we were close to others we were still able to carry on a private conversation.

“How does your sister?” Will asked, a bit formal. He seemed restrained somehow. Unusual. Maybe we needed to become accustomed to one another again. We’d never had to ere this, though.

“She’s fine, the baby comes soon. How go your studies?” I asked, maddeningly polite and distant.

“Wonderfully well. I have the opportunity to study abroad for a few months whilst my father is in Belgium for the king, and then I return home to…. study more. And to the court, of course. I will often be at court.”

“You’ll do well at court, I’m certain.”

We broke apart to dance a galliard with other partners, a quick, humorous dance that soon had the entire hall clapping, laughing, and making merry. I danced with my brother Thomas and the

n with another courtier whom I did not know but who looked at me appreciatively.

I prayed a prayer of thanksgiving for my mother and her gift of the dress. I confess that I was glad that Anne wasn’t alone in drawing admiration.

The king called for a volte to be danced, and the room shifted uncomfortably. The volte was the only dance which allowed partners to embrace. I saw the king lead Mary Boleyn—ah, Mary Carey—to the dance floor. Will swooped in before my galliard partner could claim me again, though he tried.

I softened in Will’s arms; I felt the heat of those many secret scrolls and their honest declarations as we danced. I sensed the momentum of our years of laughter and honest, heated disagreement and unspoken, deep affection.

“Meg,” he finally said, intimacy and urgency in his voice now that he’d dropped the well-mannered, unwelcome mask of civility. And there was something else in his manner, though I could not tell what. “Can we speak together outside, alone?”

“Yes!” I said. It wouldn’t be improper with so many strolling around.

“Good. Perhaps we should dance a few more songs first so as not to draw attention.”

I agreed and then unwillingly let go of his hand as the dance ended. I could feel his reluctance to let go, too.

We met outside the main door and then walked, hand in hand, to a bench just outside in the close gardens. The rain of the earlier evening had dried to a mist on the petals of the flowers nearby; the sky had cleared to a cool, starry evening. Will picked a daisy and put it in my hair, a tender gesture of love and possession that I welcomed. “Do you remember your wreath of daisies?” he asked.

“I do, and I’m pleased that you do as well.”

“I have news, Meg,” he said after a moment. My back stiffened at the tone of his voice.

“You’re to be married,” I said, cutting directly to my worst fear.

“No…. not exactly.”

“Not exactly? Marriage is a clear thing. You’re either married or you’re not.”

“My father has been spending a lot of time with the king,” Will said.

To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn

To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn